Secondary dominants are common compositional devices in all kinds of music, from jazz and classical to rock and blues. However, if you are new to music theory, you might not know what secondary dominants are or how they function.

Don’t worry! We will break down secondary dominant chords and how to use them so you can strengthen your understanding of music theory, utilize secondary dominants in your own compositions, and identify secondary dominants as you encounter them in the wild.

Want to take your music theory and jazz chops to the next level? Check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle. The Inner Circle has everything you need to break through practice plateaus and seriously improve your jazz playing.

Improve in 30 days or less. Join the Inner Circle. Join The Inner Circle.

Table of Contents

Defining Secondary Dominant Chords

image source: Wikimedia Commons

First things first, we need a definition. But before we define secondary dominant chords, we need to define basic dominant chords.

What is a Dominant Chord?

A dominant chord is a diatonic chord built from a major scale’s fifth degree. Let’s unpack that. First, let’s define diatonic chords.

Diatonic harmony is a system of harmony that constructs its chords using the notes of the major scale or natural minor scale. Each chord in a major or minor key can only contain notes from that specific key signature.

In our example, we’ll use the key of C Major and the key of A minor because there are no sharps or flats.

Each major and minor key has seven chords because every major and natural minor scale contains seven notes.

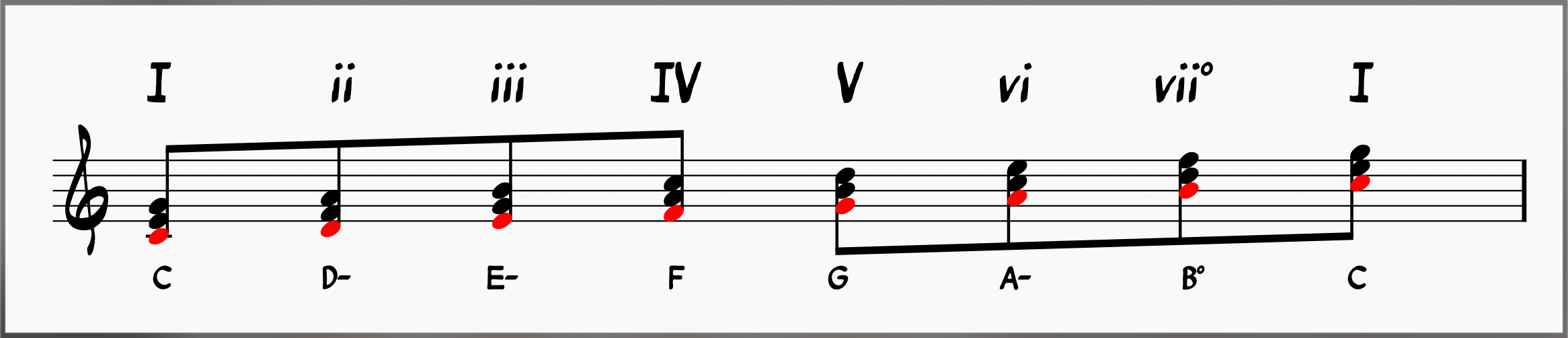

Major Diatonic Series

The chords built from the scale degrees of the major scale are known as the major diatonic series. Notice the major scale in red below harmonized in thirds to make triads. All of the notes in all seven of the following chords are from the C major scale.

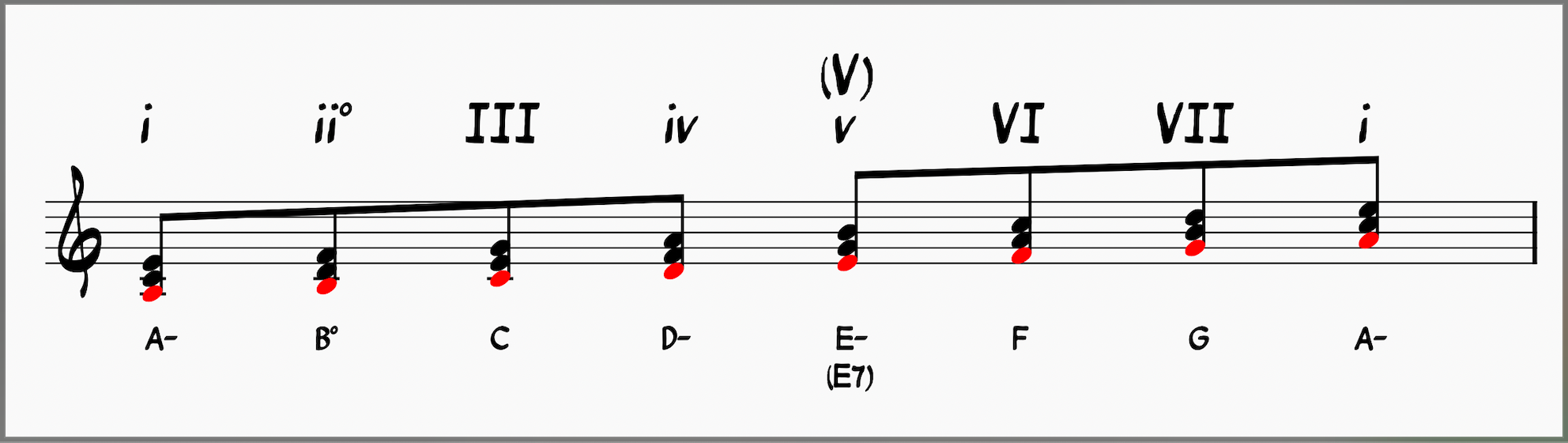

Minor Diatonic Series

Likewise, the chords built from the minor scale are known as the minor diatonic series. The natural minor scale is shown below in red. I’ve included the harmonic form in parenthesis. The harmonic form makes the v chord (a minor chord) into a V chord (a major chord).

If you didn’t know, the keys C major and A minor share a key signature, meaning they are made from the same notes and share the same chords. This is a concept called relative keys. Learn more about relative keys by checking out this article on relative minor.

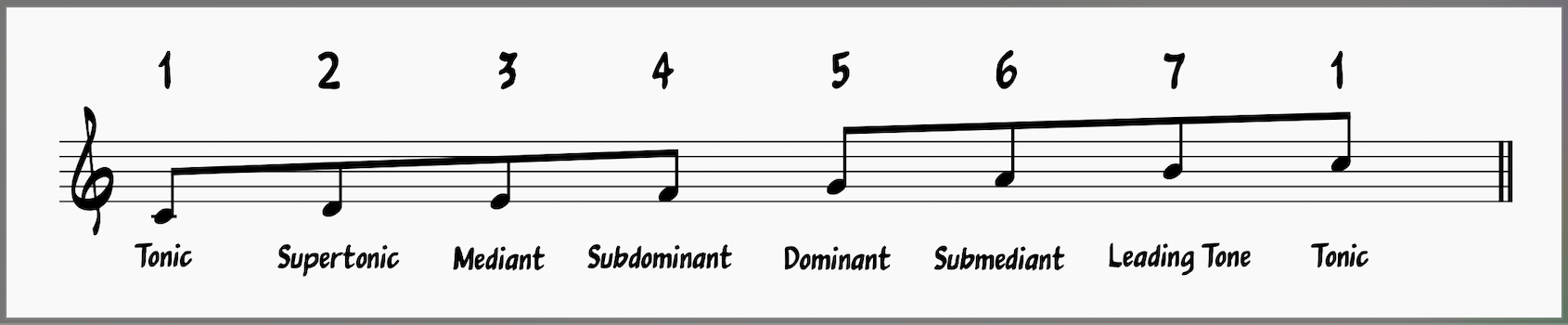

The Names Of The Scale Degrees

Here is our definition from earlier: “A dominant chord is a diatonic chord built from a major scale’s fifth scale degree.” We now know what “diatonic chord” means, but we still need to learn about scale degrees.

Below is the C major scale with all the scale degrees numbered and named according to their function.

Each scale degree and associated chord has a unique name that helps musicians quickly identify its function.

- 1st scale degree: Tonic Chord

- C major (I chord)

- 2nd scale degree: Supertonic Chord

- D minor (ii chord)

- 3rd scale degree: Mediant Chord

- E minor (iii chord)

- 4th scale degree: Subdominant Chord

- F major (IV chord)

- 5th scale degree: Dominant Chord

- G major (V chord)

- 6th scale degree: Submediant Chord

- A minor (vi chord)

- 7th scale degree: Leading Tone Chord

- B diminished (vii° chord)

As you can see, a dominant chord is built from the fifth scale degree. In the key of C, that would be a G major chord. This dominant chord has a dominant function that helps chord progressions return home to the tonic chord (I chord).

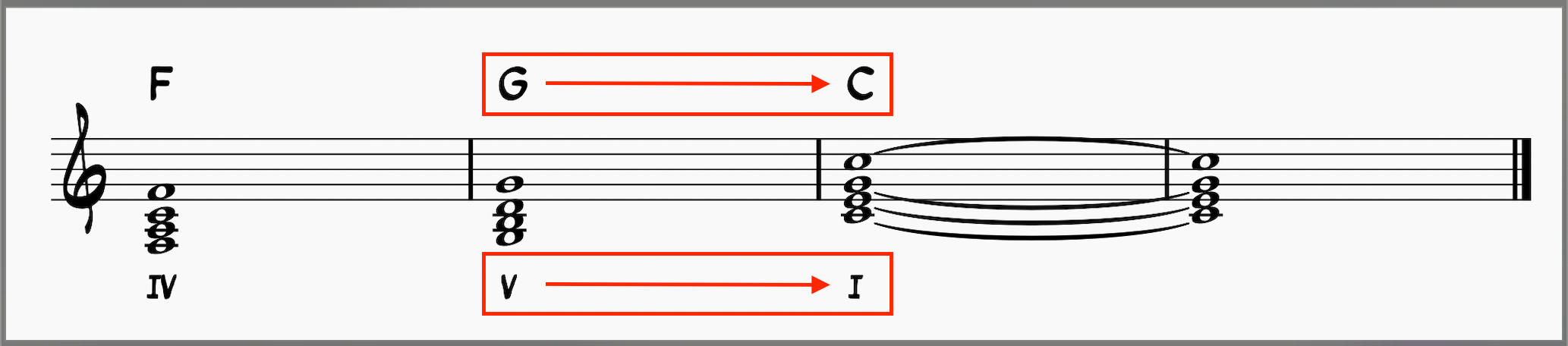

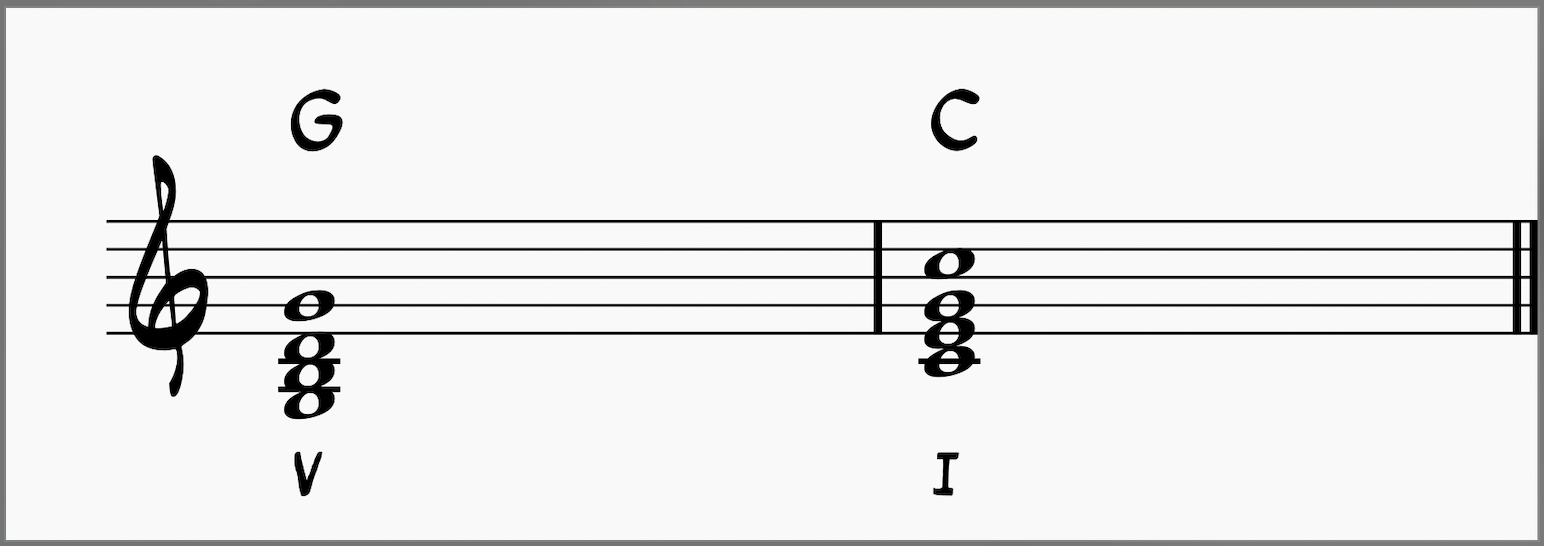

Here is a sample IV-V-I chord progression in the key of C:

Listen to the resolution from G major to C major. That is the function of the dominant chord. It has the strongest pull back to the tonic chord compared to other cadences.

V-I Cadences

This V-I chord movement is a type of cadence, the official term for harmonic resolution. V-I cadences are called authentic cadences because they have the strongest resolution to the tonic. Other cadences, like the IV-I cadence (or plagal cadence), don’t have as strong of a pullback to the tonic chord.

The V-I resolution, or authentic cadence, is fundamental to understanding secondary dominants! As you’ll see, secondary dominants are “V-I cadences” whose “I chord” is not the tonic! But, before we get there, we need to talk about dominant seventh chords.

But What About Dominant Seventh Chords?

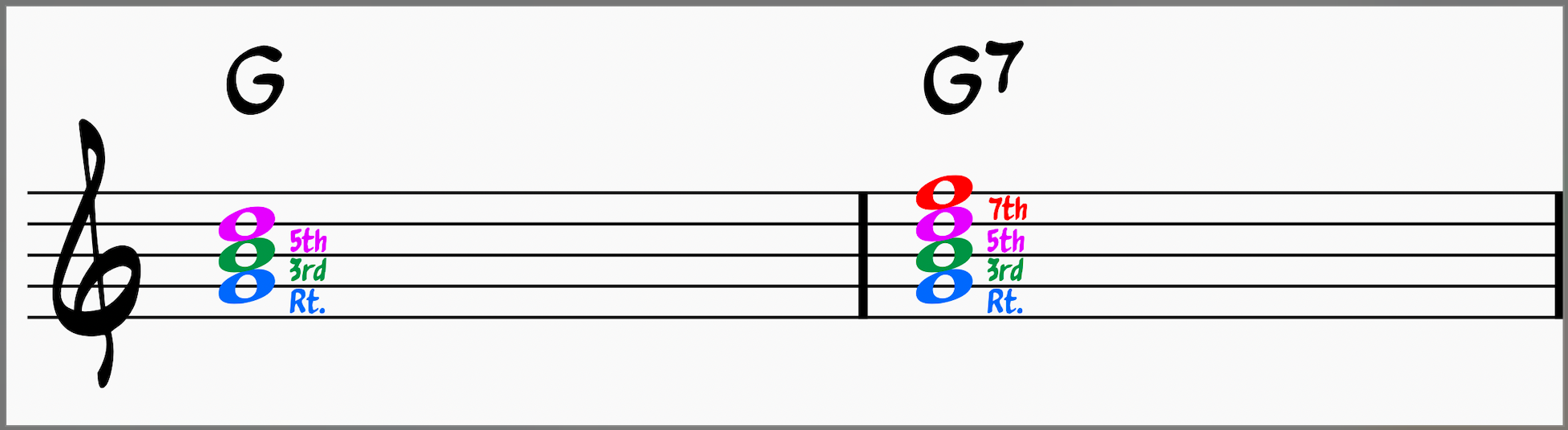

We’ve looked at major triads with a dominant function in a progression, but jazz primarily uses seventh chords. A dominant seventh chord has the same function as a major triad with a dominant function.

In other words, G major and G7 share the same function in the key of C—they are both versions of the dominant chord.

However, seventh chords contain an additional piece of harmonic information that strengthens the resolution back to the tonic. Whereas a triad includes a root, a third, and a fifth, a seventh chord has a root, a third, a fifth, and a seventh.

Adding an F into the mix creates a tritone interval between the 3rd (B) and 7th (F) chord tones. This creates a higher level of tension within the dominant seventh chord and makes for a more satisfying resolution to the tonic.

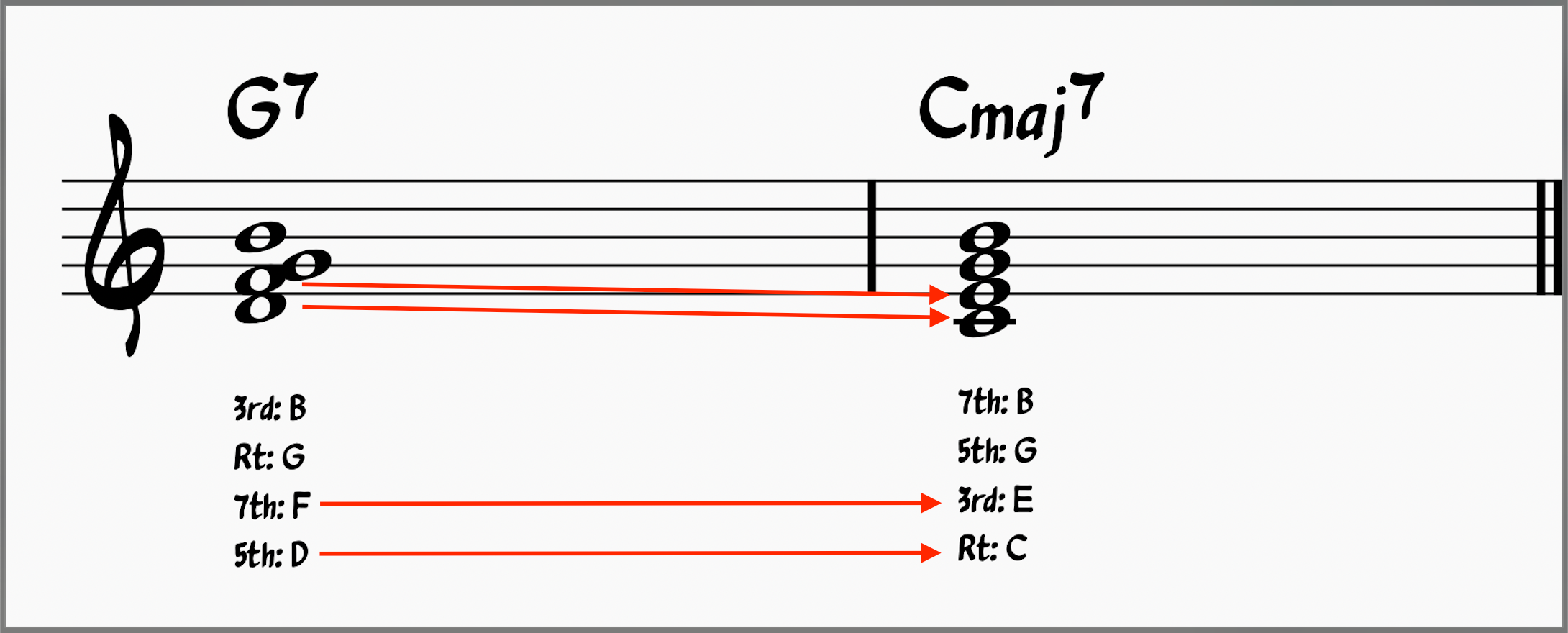

Here we have a second inversion G7 chord (G7/D) resolving to a root position Cmaj7 chord:

When a dominant seventh chord resolves, the tritone between the 3rd (B) and 7th (F) chord tones resolves to a perfect fifth. B stays the same, becoming the 7th of Cmaj7, and F moves to E, becoming the 3rd of Cmaj7.

Check out this article for more on seventh chords.

BEFORE YOU CONTINUE...

If music theory has always seemed confusing to you and you wish someone would make it feel simple, our free guide will help you unlock jazz theory secrets.

So, What is a Secondary Dominant Chord?

A secondary dominant chord is a dominant seventh chord or dominant functioning triad found on any scale degree but the V, which resolves up a fourth to any scale degree but the I. Essentially, it is a V-I cadence that doesn’t start on the V and doesn’t resolve to the I.

A secondary dominant chord is a type of chord substitution that briefly tonicizes a non-I chord from the key. In music theory, we use the phrase “V of x” to refer to secondary dominants. This helps us quickly identify the function and target chord in a chord progression.

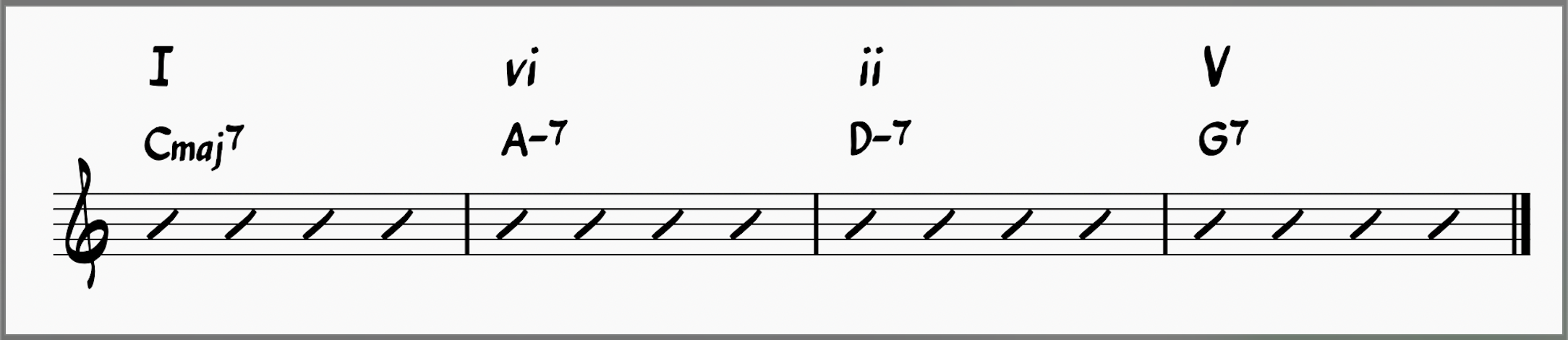

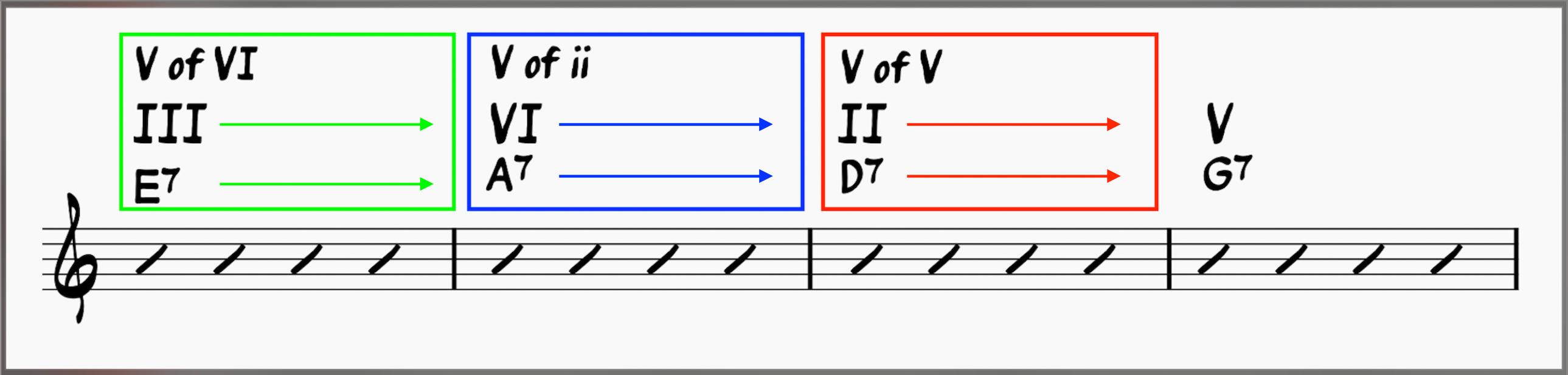

Here is a run-of-the-mill I-vi-ii-V chord progression.

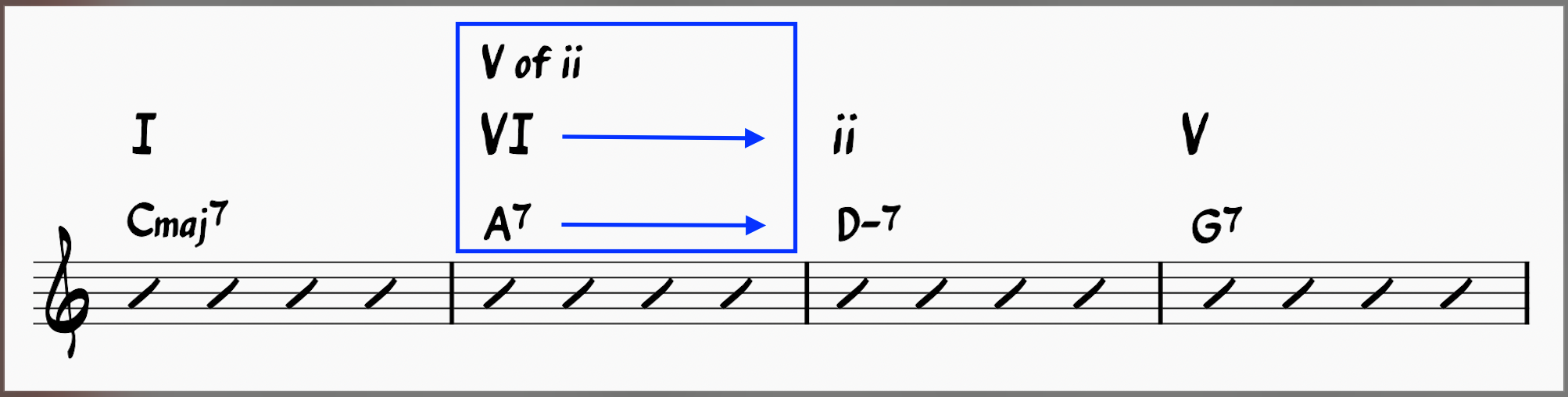

Let’s say we changed the A-7 to an A7. This creates an authentic cadence between the VI chord and the ii chord, which becomes tonicized. We would say that the A7 chord is the “V of ii” because there is an authentic cadence between these two chords.

In this I-VI-ii-V chord progression, the A7 functions as a temporary dominant.

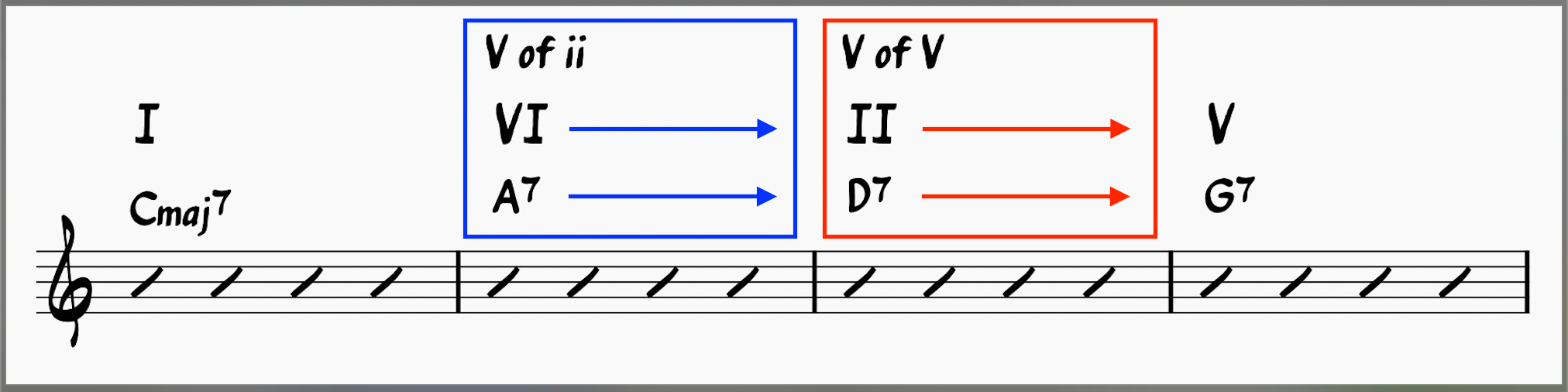

Let’s add another secondary dominant to this chord progression.

We’ll change the ii chord to a II chord. By making the D-7 chord a D7 chord, we briefly tonicize the G7 chord. In this example, the D7 chord is a “V of V” because we have an authentic cadence between D7 and G7.

Now we have a progression with two secondary dominants:

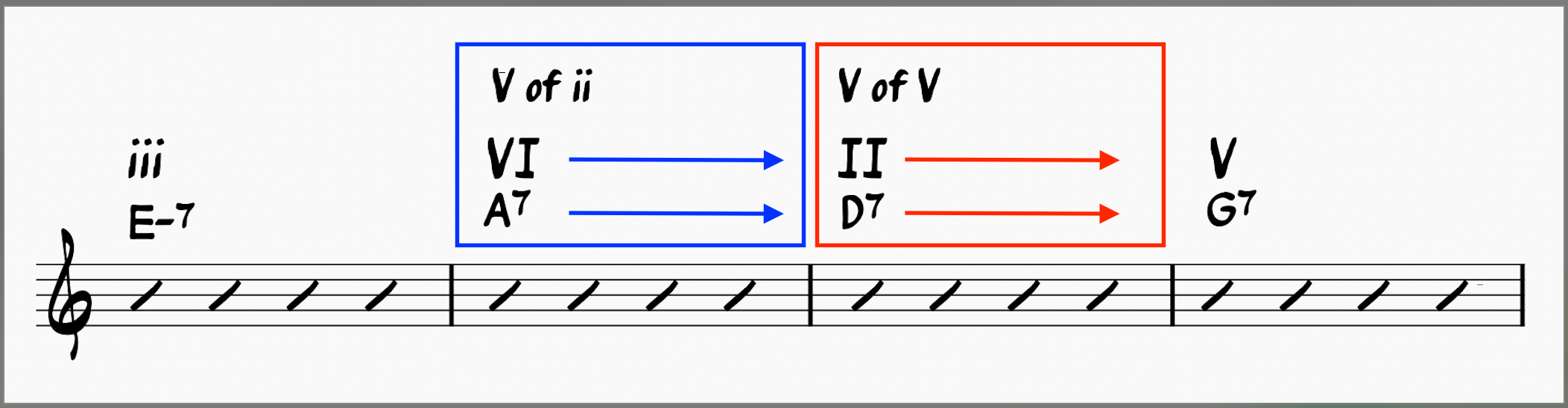

If we change the I chord at the beginning to an iii chord, we can add another secondary dominant chord to this chord progression.

Changing Cmaj7 to E-7 gives us the opportunity to add another secondary dominant chord to our progression because our E-7 will resolve up a fourth to A7. By making the E-7 an E7, we end up with another secondary dominant chord—a “V of VI” chord.

Now, we have three secondary dominants in our progression:

Secondary Dominants, Key Changes, And Borrowed Chords

Despite what you may think, secondary dominants don’t technically signify key changes like a proper key modulation. All the chords are still rooted to the scale degrees of the major key, despite there being accidentals in the diatonic chords that change them into secondary dominants.

A secondary dominant chord doesn’t trigger a whole new series of chords based on a different major scale. All the chords are still rooted in the diatonic notes of our original key—C major in our case.

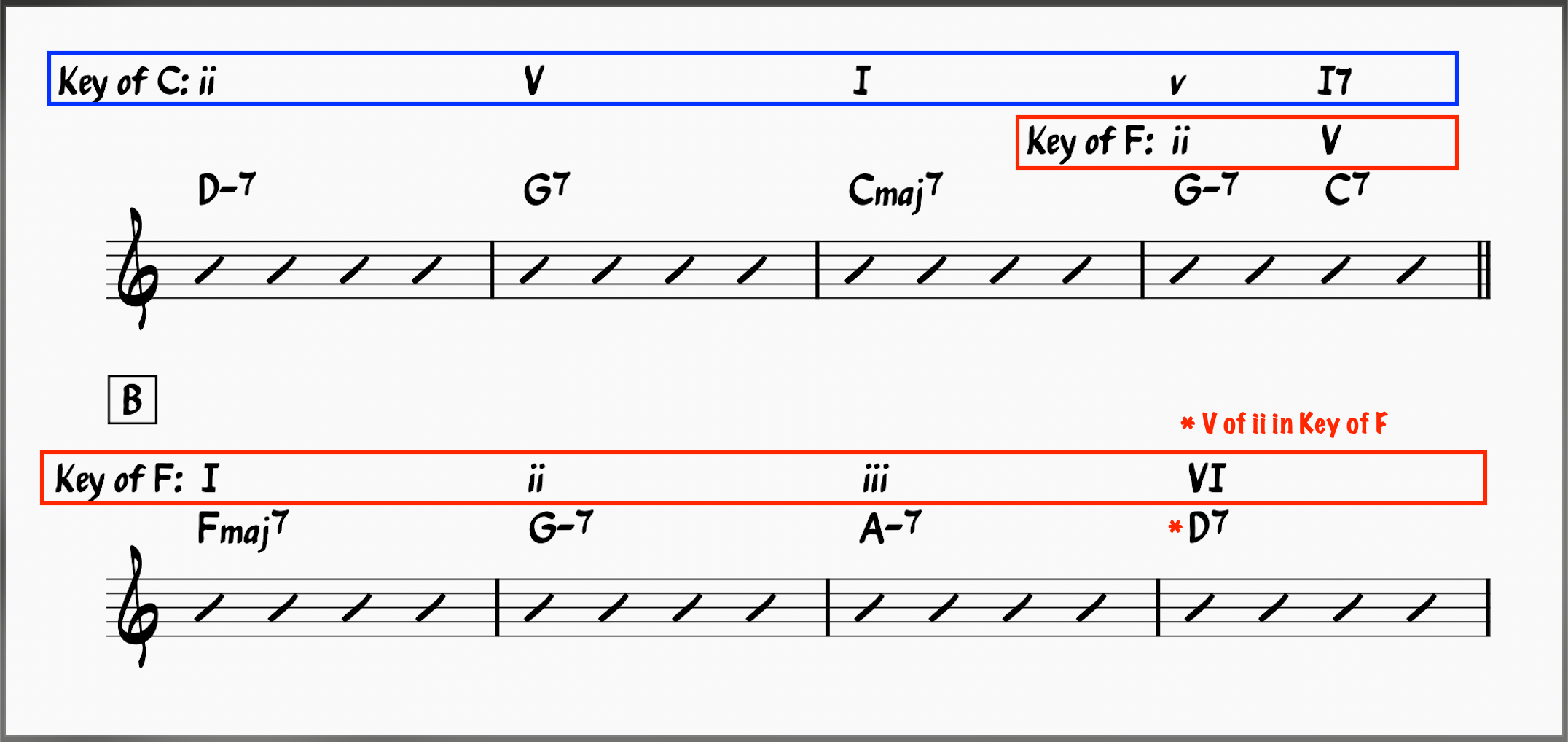

Here is what a true key modulation looks like:

The chord progression above shows the last four bars of an A section and the first four bars of a B section. We start in the key of C major but modulate to the key of F with a ||G-7 |C7 || in the fourth bar.

After this ii-V in F, we are consistently in the key of F for the duration of the four bars. This is very different than a brief tonicization of a chord by preceding it with a secondary dominant. Notice the secondary dominant in the last measure of our example.

This is a V of ii chord, and we can expect it to lead to G-7.

Check out this article for more on jazz chord progressions.

What About Borrowed Chords?

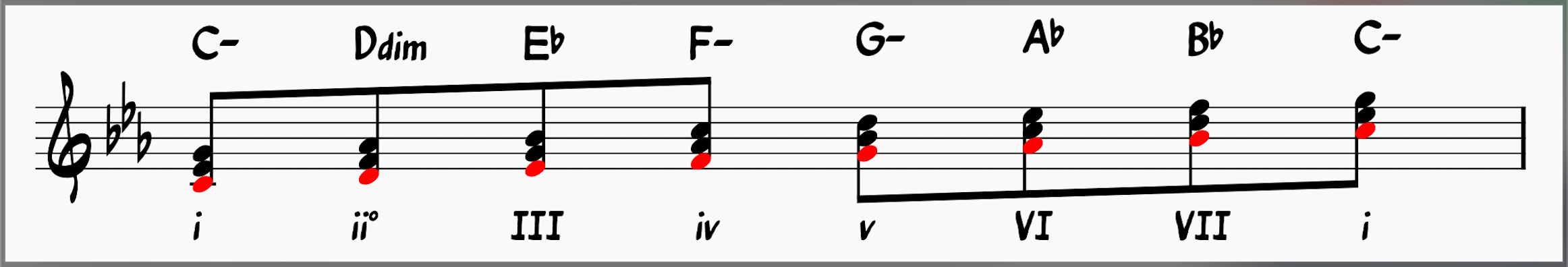

Borrowed chords are different than key changes and secondary dominant chords. A borrowed chord is another type of chord substitution, where a chord is “borrowed” from a different key. Usually, that key is the parallel minor key (but it doesn’t have to be).

A parallel minor key shares the same root note as its parallel major key.

C major’s parallel minor key is C minor, which has three flats: Bb, Eb, and Ab. This creates a different harmonic landscape that composers can utilize.

The minor iv chord is a common borrowed chord found in many chord progressions. When you see an F- chord in a song that is otherwise in the key of C major, you know the composer has borrowed the F- from the key of C minor.

Check out this article for more on parallel minor keys and this one for more on chord substitutions like borrowed chords or secondary dominants.

Join The Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle to Take Your Jazz Playing To The Next Level

Looking to seriously improve your jazz playing and musicianship skills? Check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle. We have everything you need to take your jazz chops to the next level.

Improve in 30 days or less. Join The Inner Circle.